Formal and Informal Authority and Roles

Getting “meta” with authority and roles is where big pay-offs are possible. Within the BART system, formal and informal (or explicit and implicit) versions of authority and roles always exist. So, solving organizational conflicts is often a matter of teasing out the tensions between the two levels.

Ever met a program manager or engineer who everyone on the team listens to ... though they’re not the designated lead? If a team doesn’t authorize the designated leader to lead, the leader—and, thus, the team—will be ineffective. Even if the organization has delegated formal authority by, say, bestowing a title, teams often make bottom-up decisions to follow someone whose vision they trust. That’s how informal authority usurps formal authority every time: trust always trumps a title. Despite workers believing that managers have all the power, it’s actually a two-way street, because a rogue team can negate all a manager’s efforts. Cultivating informal leaders—and their influence—is one way to acknowledge workplace realpolitik.

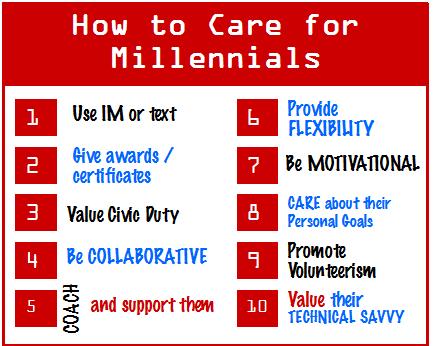

Consider all the different roles that comprise a well-functioning team. Explicit roles are engineer, QA tester, and product or program manager. But informal roles are where organizational dynamics are powerfully at play. What if your program manager (explicit role) doesn't take up the task master role (implicit)? Or what if your tech lead is so busy writing code she isn't directing the team? Class clowns grow into comedians at work, defusing tensions via a sort of court jester loophole. Who’s the social coordinator? Who’s the unofficial “jerk” or “devil’s advocate” (where ideas go to die)? (Maybe you’re the informal leader?)

(People get stuck in unofficial roles, too. Does the “giving” type at your office always end up with grungy clean-up tasks or with serving as morale-booster? How long before that person burns out, if their unofficial role is draining—as well as unacknowledged?)

Tasks

Official tasks are pretty much what you’d expect: write code, test code, launch products, etc. If you’re schooled in organizational dynamics, you’ll see plenty of unofficial tasks, too. Temporary groups, convened for a finite purpose or task, are sometimes subject to a counter-intuitive dynamic: survival!

The team wants to survive as a team, the start-up wants to survive as a start-up. Group-members start thinking (subconsciously), “I’m important because I’m in this group ... so I’d better ensure the group persists.” They become preoccupied with the group’s longevity and health (so their important role as group-member will persist), rather than with whatever putative task they’re supposed to accomplish. When this task takes over, unintended consequences arise ... such as the engineer who polishes the same section of code over and over, instead of moving on. Once you know the concept of unofficial tasks, they’re a lot easier to spot.

Dysfunctional Dynamics: A Case Study