Assessing the Inter-Generational Work-Force

/“Know Thyself” and “Do Unto Others”

Who are we? Why do we behave the way we do?

Along with Why are we here? these are the most basic questions humans ask.

Many schemes try to explain how we’re “wired”—that is, our basic “default settings” for behavior and interactions. From reductionist systems like astrology to more complicated frameworks such as psychoanalysis, the ubiquity of these systems shows us just how much we want to understand ourselves—and others.

Evolved managers use “know thyself” as a precept, and help their teams understand their own—and others’—needs and behaviors better, too. One tool that helps contemporary managers develop and lead an intergenerational workforce began as research on combat teams during the Korean War. And it may make you question one of these precepts.

Most US Companies Use Some Type of Assessment Tool

The work world must ensure different people function well enough together to fulfill a company’s mission, and has often scrambled to find and use systems that can illuminate ‘types’ and predict behavior.

Many assessment tools have been around for decades. The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI for short) is used by “89 of the nation's Fortune 100 companies,” according to Jennifer Overbo, director of product strategy for CPP Inc., the MBTI’s publisher.

by AON "Leadership Assessment The Backbone of a Strong Leadership Pipeline" April 2015 http://www.aon.com/attachments/human-capital-consulting/Leadership_Assessment_Backbone_of_a_Strong_Leadership_Pipeline.pdf

Situational Leadership, for instance, as the name implies, is geared specifically toward leadership development. Among myriad other assessments are Disc, 16Types/BigFive, Hexaco, Strengthsfinder, and HoganLead.

A Multi-Generational Workplace Adds Complexity

Even with relatively homogenous work-forces, assessment tools have been popular for decades, but the rise of the multi-generational workplace has ratcheted up the need for clarity about differing attitudes and priorities.

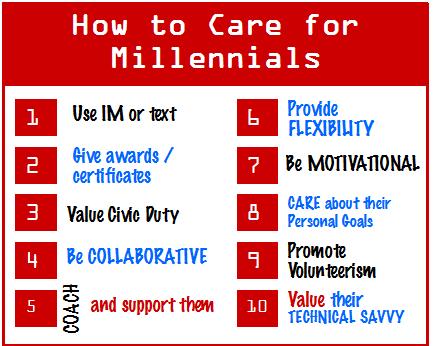

In fact, as the following graphics make clear, from academia to think tanks to LinkedIn, much effort is being dedicated to analyzing and documenting generational differences—so each faction can be communicated with, motivated, and acknowledged appropriately.

Source: Posted by Merry Selk (Strategic Communications / Content Strategy) citing Jennifer Patterson (Mobile Solutions Professional @ T-Mobile) citing Georgia Tech (GIT) President G. P. (“Bud”) Peterson’s content #FF2016

Personality vs. Behavior

Given how many companies want to manage their workers productively, chances are you’ve taken some sort of “personality test” at work. (They’re formally called “assessment tools,” but earlier iterations of instruments tried to describe overall personality, hence the popular term.)

I’ve taken many assessments myself, and, as a coach who administers these tools, am familiar with many more. I appreciate that newer tools go beyond such traditional emphases as whether you’re an introvert or an extrovert to focus more on how your needs affect your communication style and behaviors at work. This narrowed focus doesn’t try to map out complete personality types but instead lasers in on specific aspects of how you operate within groups.

An assessment tool that works well with today’s multi-generational workplace is the FIRO-B (Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation).

Why FIRO-B?

Developed by psychologist Will Schutz, the FIRO-B framework evolved at the American Naval Research Laboratory. (Schutz’s colleagues included Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, and he eventually worked at Esalen and wrote several books on group dynamics.) Selected by the Navy for his research reputation in group dynamics, Schutz was asked to model how teams would perform in combat.

Though I hope your workplace isn’t a war-zone, FIRO-B (FIRO rhymes with Cairo) offers teams a way to explore motivations, conflict, and mixed messages. “It also reveals ways of improving relationships by showing individuals how they are seen by others, and how this external view may differ from how they see themselves.” Because it emphasizes group dynamics, and differing needs, it offers the inter-generational workplace “an efficient way to encourage self knowledge and improved team-work.”

The FIRO-B assumes that behavior arises from an individual’s differing levels of need for involvement, influence, and connection, which then play out—often messily—in groups.

The latest version of FIRO-B emphasizes B for “business” (the original “B” stood for “behavior”). It measures preferences within two modes: “expressed” behavior (i.e., when you initiate action) and “wanted” behavior (i.e., when others initiate action) for your needs for involvement, influence, and connection.

“expressed” behavior (i.e., when you initiate action)

“wanted” behavior (i.e., when others initiate action)

Expressed Behavior

How much do you prefer to initiate the behavior?

How do you actually behave with respect to the 3 fundamental interpersonal needs?

What is your comfort level engaging in the behaviors associated with the 3 needs?

Wanted Behavior

How much do you prefer others to initiate the behavior?

How much do you want to be on the receiving end of those behaviors?

What is your comfort level when others direct their behaviors associated with the 3 needs to you?

What motivates our behavior regarding how much interaction we want with others? It can get a little confusing. The video below shows how knowing about intrapersonal needs can give us a better sense of why we avoid—or seek out—certain situations, and how we come across to others.

I like the FIRO-B because it addresses the need for “inclusion” (involvement) and “control” (influence) directly, and thus helps answer what kind of work cultures you’ll function well in—and in which you won’t.

When you take the assessment, you may be surprised at your different numerical ratings for the three needs on the “wanted” and “expressed” grid. For instance, who wants to be called a “control freak? But, those who claim Janet Jackson’s “Control” as their anthem are plentiful in the workplace. But when you move beyond the basics, things get more interesting.

You may score high on how much control you want when you initiate a project, for instance, and low when someone else initiates a project. The devil’s in the details. Learning the difference between what you can control, and what you can’t—and when it matters and when it doesn’t—is a must, not just in your personal life, but in the workplace.

Control and Inclusion: Boomers/Gen X vs Millennials

Think about the generational lists above. Sure, they’re generalizations. But different generations, in aggregate, do tend to have different values, overall. Nobody confuses hippies, yuppies, or techies. Differing degrees of how much we express vs. want control and inclusion significantly affect interactions in the multi-generational workplace.

What kind of needs for control go along with "do not micro-manage" (Millennials). How about independent Gen X-ers? What kind of control do you think they exert (vs. what amounts of control do they want exerted over them)? Personal and generational preferences can combine bewilderingly.

When Boomers or Gen X-ers manage Millennials, for instance, a frequent complaint is how entitled they seem, or that they pick friends (connection) over work. At the other end of the continuum, Millennials managed by more experienced staff often bemoan hierarchies, and overly-directive styles, especially if they’ve not been privy to decision-making. “Why didn’t he ask me for my opinion before organizing that project?” a Millennial team-member mutters about his Boomer boss. “I probably know more about it than he does. Why am I never in the loop?”

It may help older managers to remember that Millennials grew up being included in family decision-making. The parenting style in fashion as they came of age (in the US, at least) meant their input was solicited during family interactions. In fact, the Millennial default setting is participation and involvement, so a more distant, formal management style may feel disrespectful of their skills and preferences.

Those with differing preferences within each generation for both expressed and wanted behavior would do well to assess themselves and then explore the differing needs for inclusion/influence and control/involvement in their direct reports, team-mates, and bosses.

Are You in the Right Place?

Let’s imagine inclusion/involvement and control/influence on a continuum.

At a large company, launching even a small project usually entails consulting one’s boss. An engineer who wants to initiate a small new feature probably has to sell a product manager internally before presenting it to her engineering peers. For a larger project, the buy-in list may include a boss, that boss’s boss, HR, other teams, etc.

Fed up with work? Analyze why it is frustrating...

This can be frustrating for someone who needs a lot of control and has few needs for inclusion. She may be better off as, say, a consultant working from a home office, since she’d be able to control what type of work she accepts, and structure her own work-day and tasks.

Conversely, someone with low control needs but very high inclusion needs might thrive at a large company where he may not have too much say over how projects are initiated and completed, but would enjoy a high level of participation via near-constant team interaction.

If you like a lot of control, ideally you’re in an environment with lots of processes. Someone who feels control is “inflicted” on them might instead thrive in the “chaos” of a start-up, where you’re launching product according to what customers need every month (vs. what engineering needs).

Checklist

If you’re a manager using FIRO-B to coach your team, try asking questions like these:

Where are areas in your work where a high “wanted” control number reflects the work-place reality? How about a low “wanted” control number?

How about areas where your “expressed” control number is useful? Give an example of someone on your team.

What’s an example of your “wanted” level of inclusion? (i.e., Do you want to be asked to come to lunch?) What about project inclusion?

- Who has the highest” expressed” inclusion numbers in the room? Why? Is it true? What are examples of “expressed” inclusion?

“Do Unto Others”... Sometimes

As we develop ourselves and help others develop as leaders, keep reflecting on how generational values affects individual character. Don’t over-generalize, but realize that the common zeitgeist can heavily influence the assumptions and expectations of people who came of age within a generation.

FIRO-B can encourage team-members to discover their own preferences and behaviors, and those of their colleagues, especially when they’re not necessarily intuitive. Realize that how people act toward others is not necessarily what they want reflected back to them. Never assume, and always discuss (which is a good strategy for life beyond work, as well.) Clarifying how best team-members best get their needs met isn’t just good for them, it reduces troublesome dynamics, and enables discernment about the right fit for the individual, the group, and the organization.

It turns out that “do unto others” isn’t always applicable, but “know thyself” is.