Engineering Leaders: Don’t Sabotage Your Own Team

/We’ve all worked with that super-smart colleague or manager who makes our life miserable. The clueless co-worker is a trusty cultural meme — from Dilbert to myriad sit-coms to the avalanche of “self-help” books guaranteed to help us survive the crazy in the next cubicle — showing again and again what we know intuitively: smart doesn’t necessarily mean successful. In fact, EQ rather than IQ predicts success at work.

Yes, I Used the ‘E’ Word

The idea of Emotional Intelligence has been around for a generation. (I know… I said the ‘E’ word, but hear me out.) Popularized by Daniel Goleman, EQ (emotional quotient) is now acknowledged to usefully gauge qualities that have proven more reliable than IQ to correlate to success. A high EQ means you combine self-awareness and social awareness to interact successfully with others, by staying aware of your — and their — emotions and motives, and managing your behavior and relationships accordingly.

Especially in environments where traditional high IQ is a given, such as engineering teams, EQ is the differentiator among average, successful, and stellar performers. TalentSmart, for example, tested EQ “alongside 33 other important workplace skills, and found that emotional intelligence is the strongest predictor of performance, explaining a full 58% of success in all types of jobs.”

Engineers Don’t Need No Stinking EQ

To those protesting that “hard” skills are everything, here’s a reminder from a post titled, “The Emotionally Brilliant Engineer”: “Technical skills are definitely critical … [but] … engineers have to work with others. They have to pitch ideas and defend them. They have to work with people outside their field. Communication is absolutely critical for engineers. Having a strong ability to read the emotions of others and being aware of your own emotions is key to your success.”

But what if your engineering team leader (um, you?) is an emotional dullard? The good news is that EQ — unlike IQ — can be changed. Learning how to raise your EQ pays off personally (people with high EQ average almost $30K more per year than their non-high-EQ peers). It also helps with what Google says is the #1 key to a successful team: psychological safety.

After over 12 years as an engineering manager, and now specializing in coaching and mentoring, I offer my peers a caveat: don’t let your own low EQ damage your team’s psychological safety — and hence success. If you can’t self-regulate your response to your emotions well, you compromise your ability to stay aware of those emotions. This affects your flexibility in re-directing your behavior. And that puts not just you but your whole team at risk.

Low-EQ leaders who derail what might have very successful outcomes? I’ve seen it countless times. One colleague described a manager of another team as an “alcoholic father.” Everyone in the team covered for the manager, ensuring he looked good: they said things were good and that they liked working for him. But the observation from the outside? The manager was abusive not only to his staff but to his peers. Only after folks stopped working for him on that team did they notice how much less stressful life was.

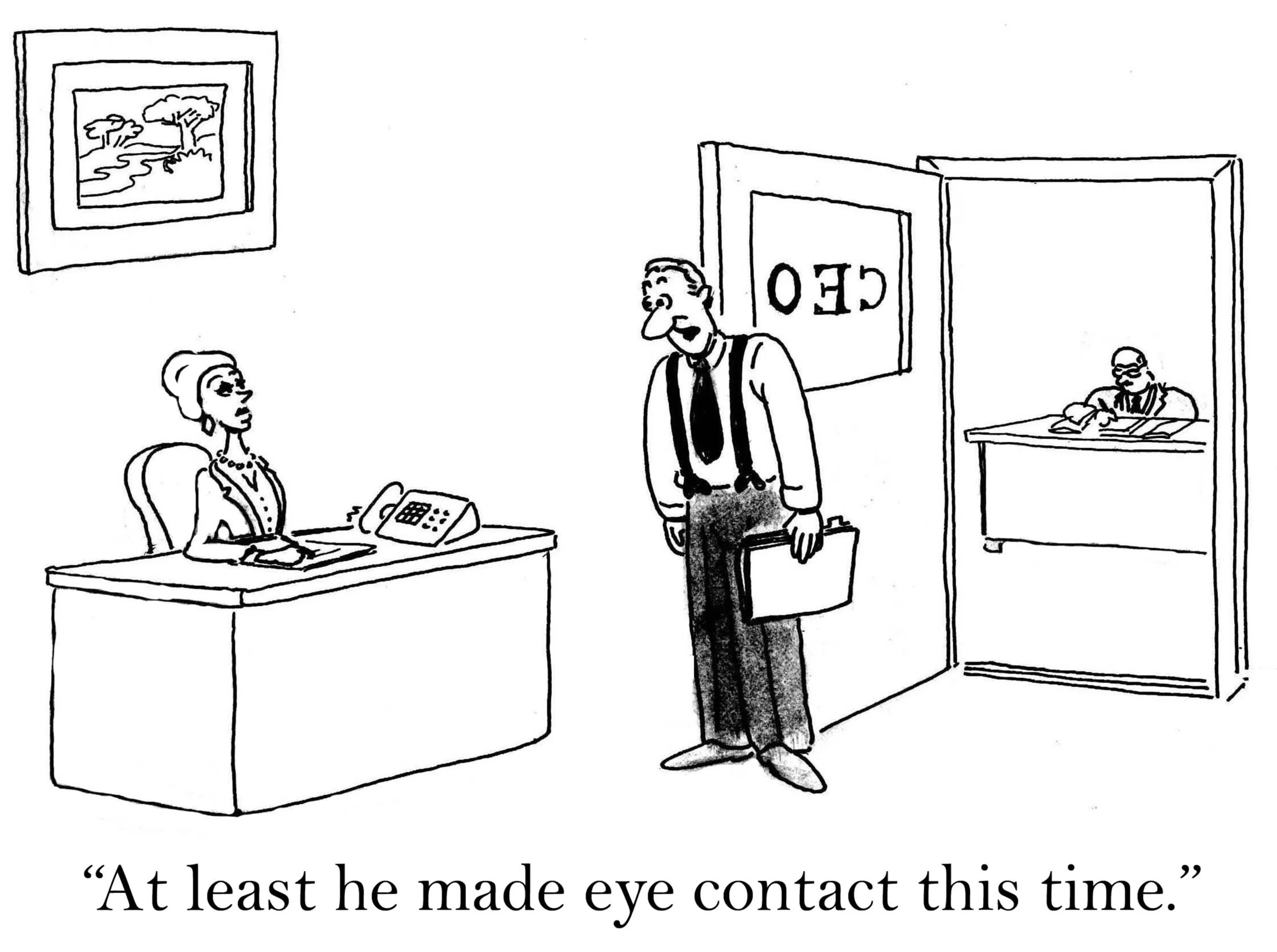

I’ve also witnessed engineering leaders so brutal that folks quit approaching them for feedback. The engineers I know tend to see things in black and white. If transparency and feedback are the espoused value of the organization, so their reasoning goes, isn’t brutal honesty the most efficient tool? No, because even frank feedback must be delivered in a way the receiver can absorb. If brutal honesty triggers arguments, with feedback recipients defending their solutions because they feel attacked, everyone loses. The leader’s sub-par EQ tanks the engineer’s benefiting from the feedback — and solutions to the actual project at hand are lost.

If you don’t know yourself — foibles, prejudices, triggers and all (as well as how you come across to the different personalities around you) — how can you manage your own behavior to ensure not only competent but inspiring leadership? You can’t. So raising your own EQ and ensuring psychological safety for your team go hand in hand.

Raise Your Own EQ

To get started, I suggest an EQ assessment by Hay Group, MHS, or TalentSmart. An EQ assessment scores your different EQ factors so you know where to start shoring up. It helps you work on your self-awareness to ensure you realize what’s happening while it happens. Do you get overly competitive when people on your team ask you questions? When you get competitive, or are challenged, can you self-regulate? Or do you start lashing out?

Do you have enough empathy or social awareness to understand the impact of your behavior? Perhaps you do, but how do you know? You depend on other people to tell you. And that doesn’t normally happen in the moment — it happens as feedback … later. But when I get vague feedback months later (e.g., “be more collaborative”), I have no idea when, where, and with which people. Just like a good parent or dog trainer, leaders must offer feedback at the right moment, and it must be specific and actionable. If someone knew I was working on self-regulation, for instance, that person could say right after a meeting, “Hey, you took over in that meeting, and I saw people shutting down. Did you notice?”

Learning how to receive feedback is vital to developing your EQ. In the book, Thanks for the Feedback, the authors Stone and Heen show that feedback receivers are often in the wrong state of mind. But if they can get put themselves into the correct emotional state to receive the feedback as it’s intended, they can actually learn and change.

Once you start increasing your own EQ, and inculcating the practice among the teams you lead, you’re on the path to enabling a psychologically safe team.

Ensuring A Psychologically Safe Team

Amy C. Edmondson, Professor of Leadership and Management at Harvard Business School, says, “Psychological safety promotes the attitudes, skills, and behaviors needed to team.” Without it, we “rob ourselves of small moments of learning — and we don’t innovate.”

Edmondson, whose landmark book, Teaming, solidified the importance of teams in the annals of organizational behavior, defines safety as “a belief that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up when there are ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes.”

In her TED talk, “How to Build Psychological Safety,” she notes that we’re often held hostage by “impression management” or the need to appear in certain ways in front of others.

In fact, we mis-equate how to look good with behavior that’s lethal to creative problem-solving — all in an effort to avoid shame and other negative consequences. That is, to avoid the characteristic below on the left, we often adopt the attitude on the right:

- Ignorant = Don’t ask questions

- Incompetent = Don’t admit weakness or mistakes

- Intrusive = Don’t offer ideas

- Negative = Don’t critique the status quo

Understandably, most of us don’t want to seem ignorant, incompetent, intrusive, or negative. But what exactly does that mean for our behavior in teams? Unfortunately, trying always to look smart, competent, inconspicuous, and positive means we forego behavior that’s vital to healthy team-work.

Obviously, few teams can survive, much less thrive, without the fruits of these “risky” behaviors: questions, mistakes, and ideas should be par for the course in just about any human endeavor, much less high-performing engineering teams. And of course “don’t question the status quo” transmogrifies into “don’t innovate!”

Edmondson notes three simple ways to build psychological safety:

- Frame the work as a learning problem, not an execution problem. (This creates a rationale for speaking up.)

- Acknowledge your own fallibility. (“I may miss something so I need to hear from you.”)

- Model curiosity. (Ask a lot of questions.)

How This Works in the Real World: High-EQ Leaders Enable Innovative Teams

From my own experience, here’s how EQ and psychological safety work together:

I still work on noticing when I get quiet and tune out of conversations — with the goal of self-managing my response to conflict. I figured out my forehead tingles when I’m zoning out in a certain way. When people argue with each other and it isn’t going anywhere, or it’s about to get really loud, my heart rate goes up a bit, too. As I became aware of it, I could manage it.

Now, I ask myself, “What’s going on here?” or an even more touchy–feely question: “How do I feel right now?” Instead of leaping in to protect the engineer who’s being ‘picked on’ by the ‘big bad other engineer,’ I usually ask a question of the group. There are usually sighs of relief — sometimes even from the engineer inciting the conflict! Oh, yeah! We were lost in some weird conversational loop that wasn’t actually that important.

Noticing the data around you — especially when that data has to do with your body and your instinctive responses — lets you figure out and practice self-regulation. Managing your own reactions ensures your team stays safe enough to ask questions and challenge the status quo. That’s the springboard for your team to truly innovate.

Originally published on Medium.com

Disclosure: at the time of this writing, I am a Google employee; however this article represents only my own views as principal of Capriole Consulting. Nothing above should be construed as being indicative of Google’s organizational philosophy or practices.